How Loved Places are Joyful Places [Jaipur, India]

I love Jaipur. I have visited three times, and every time I am drawn to the cultural and visual energy of the city: the pink sandstone glistening in the hot sun, the deep purple shade and shadow dancing on the facades in the cool sunset, the sounds and scents from the bazaar wafting in through the open windows and courtyards, the smell of incense from the nearby temple, and the pops of colorful dresses as people walk and dance through the city. What then makes buildings and places lovable and how is love linked to our joy and happiness? In the Original Green Steve Mouzon states that "a lovable building and place reflects us, delights us, and puts us in harmony with something greater than us." Moments of joy in our lives and our cumulative happiness is always accompanied by love. We are sensitive to the world around us and our joy and happiness are dependent on our surroundings. What resonates the most for me is that Jaipur is able to reflect and impart the adored culture of India in its physical form.

In Jaipur, the joyful harmony offered in the organization of the urban fabric is unique. It is not the buildings that impose their shape on the street, it is the layout of the roads that determine the location of the buildings. The alignment of the streets allows for good air circulation, and the narrow dimensions, as well as architectural eves, enable the cooling of public spaces. The chowkris (neighborhoods) correspond to the large squares emerging from the grid of bazaars and chaupars (public squares). Inside the chowkri, the orthogonal roads lead to the mohallas which are clusters of havelis (houses) corresponding to social groups. It is customary for their size to be around 40 to 50 plots. The plots, and associated havelis, are accessible by the street and also from within the heart of the block by an intimate, semi-public common space. The haveli entrances favor the eastern and northern directions to enable passive cooling at the architectural and urban scale. Shops exist on the periphery of the neighborhoods along the bazaars, while the center of the block remains residential. The bazaar fabric is limited to two-to-four floors. This creates shade along the narrow streets while avoiding building heights that are too tall.

The bazaar galleries were the first elements constructed in Jaipur. They are the module of the city’s architecture. These galleries were intended both to provide space to the first merchants wanting to settle in Jaipur and to showcase planted avenues that were already inhabited for travelers passing through the city. This module is a result of the stone from quarries around Jaipur, which imposes a tight rhythm that is found at all construction levels. People are allowed to build on top of the bazaar shops. The upper floor haveli facades rest on a second load-bearing frame that is one step back on a large beam. This beam defines the true public-private limit between the bazaar and the haveli. This complexity adds to the sensorial abundance of the buildings and the joyful experience within the public realm.

The haveli offers its most beautiful facade to the bazaar to be seen by the public. This signifies the importance of celebrations and processions within public open spaces in India. The most sought-after havelis have projecting stone windows, porticos, and a balcony system opening up onto the streets and open spaces of the city.

The galleries offered by the bazaars as well as balconies and terraces offered by the havelis help Jaipur's building fabric and the larger public world feel intertwined. These features enable people to be in the building but in touch with the community and scene outside. Such spaces offer opportunities for households to live comfortably for hours (see San Francisco), in touch with the street - playing cards, swinging on a terrace swing, drying and folding the wash, making kites, eating, scrambling with children, and watching a wedding procession along with people dancing in the street. This feeling of being part of the street scene is also achieved with a fabric of two-to-four story buildings. Above four stories the connections start to break down (see Florence). Conscious, free-flowing dance is an integral part of celebrations and processions in India. According to a UCLA Health study, dance improved a majority of the participants’ mood. Many also reported that conscious dance gave them more confidence and compassion. Another study found that synchronized dancing with others enabled people to feel closer to each other and fostered friendship. When people dance, happy chemicals called endorphins are released and are integral in the human bonding process.

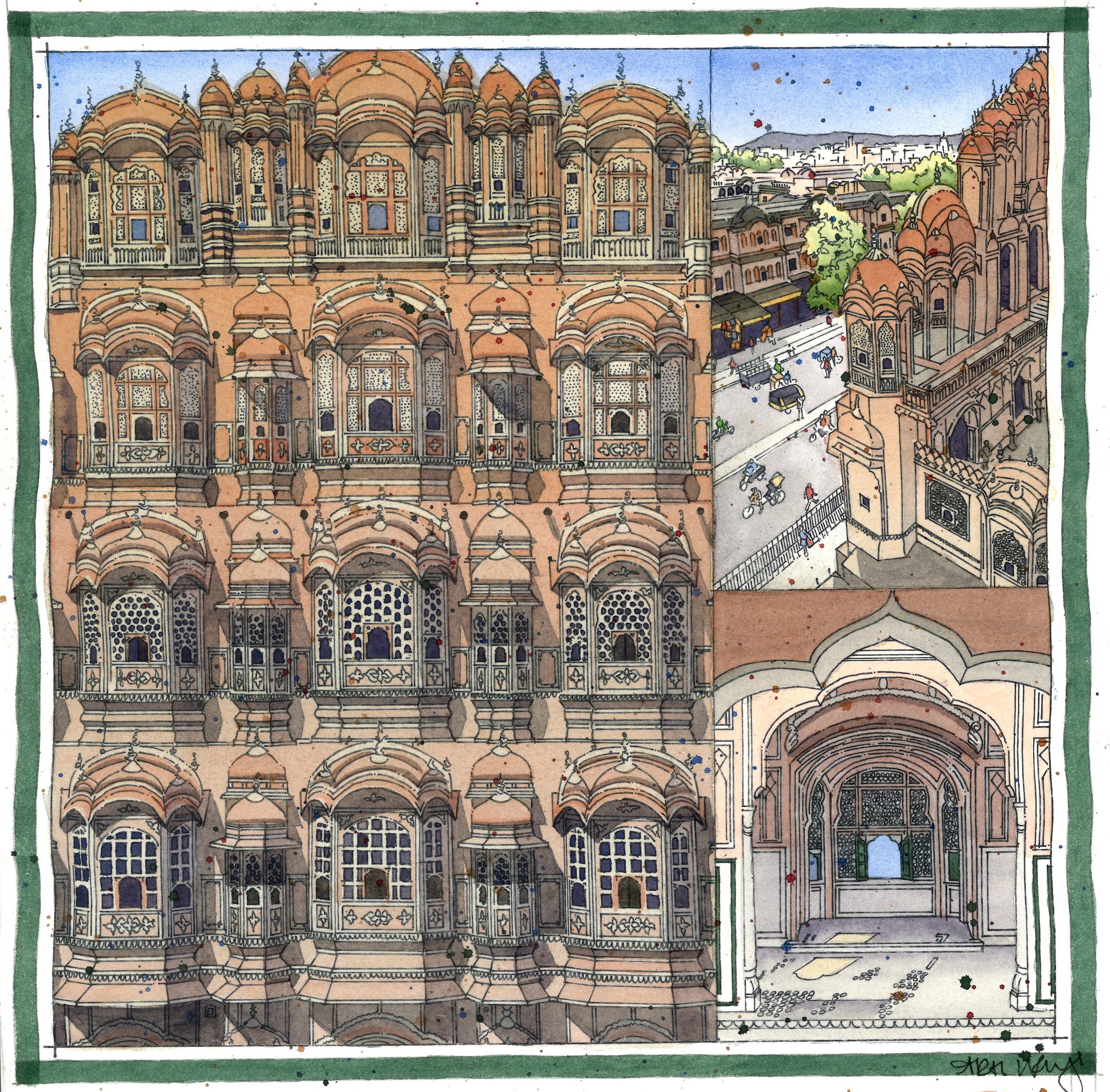

While the bazaars and havelis comprise the majority of the city’s building fabric, they also offer a background for cherished monuments, temples, and sacred sites to sparkle and imprint into our memory. Hawa Mahal has always remained close to my heart. It is a five-story pyramidal landmark that has about 900 windows on the outside walls. These honeycomb-shaped windows with beautifully carved latticework, pink sandstone balconies, and arched roofs with cornices serve multiple functions. They allow a breeze to blow through the palace making it cool and comfortable in the hot Jaipur summer and they allowed the royal women to observe and feel part of everyday life and festivals celebrated in the street below without being seen. During the time of construction, women had to obey strict rules which forbade them from appearing in public without face coverings. The unique, street-facing facade is a symmetrical massing of semi-octagonal bays. The inner facade consists of chambers and corridors with minimal ornamentation around a central courtyard. The courtyard is an essential element in the passive cooling ability of the palace and presents a sanctuary for women and children.

In Jaipur, the loved roots of the community are presented through the layout of the city, the size of plots within an urban block, the haveli configuration, the design of palaces, the preservation and design of sacred sites and temples, and the celebration of monuments. The common spiritual thread is principles explained by sacred texts of Indian architecture that are grouped together under the name of Vastu. In the case of Jaipur, Vastu is represented by the city’s layout of 9 squares around the central palace, where the north-western square was moved to the south-east due to the hillside. To understand the essence of Vastu, one must go back to the origins of Hinduism and to a myth guiding building activity. The key takeaway of the myth is that Vastu is the vital energy of the Earth and every object on it. The wholistic square corresponds to the perfect shape as a model of balance and is divided into 9 sub-squares. The 8 outer sub-squares surround and protect the center, Bhrama (the creator), and the symbolic heart of the city.

![How Loved Places are Joyful Places [Jaipur, India]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b63c07485ede1aa9c4b6ced/1647618070631-1TT7NUSYWE1U41KN4LMQ/Joyful+Urbanist_Jaipur+Hawa+Mahal.jpg)

![Your Joyful Neighborhood Street Cafe [Paris]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b63c07485ede1aa9c4b6ced/1664325736398-D9JNZKBI4G2QYN2HVG22/Joyful+Urbanist_Paris+Street+Cafe+Watercolor.jpg)

![Why Moments of Pedestrian Interest Increase Our Ability to Remain Present [Siena]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b63c07485ede1aa9c4b6ced/1624646417788-ODLQNYPWYY2C5V0P5D8H/Siena+Watercolor_Joyful+Urbanist.jpg)